COVID-19

Would systemic COVID testing at school work?

More Schools Are Doing Systemic COVID Testing. Will It Work?

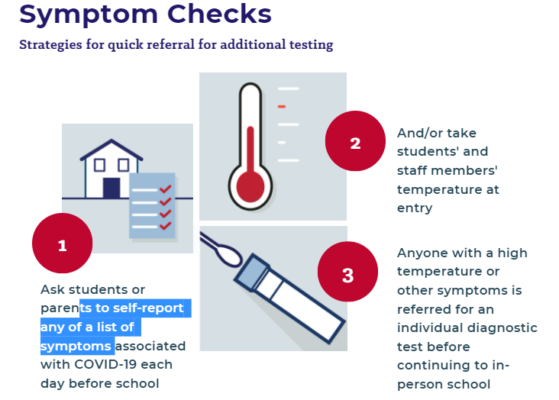

The majority of school districts rely on spotting symptoms of COVID-19 to prevent contagious students and staff from spreading the virus.

But in the perfect storm of the new school year—with mostly unvaccinated students, the exponentially more contagious Delta pandemic strain, and predictions of a bad season for colds, flu, and other respiratory illnesses with symptoms similar to COVID-19—health officials warn that basic symptom screening and temperature checks won’t be enough to avoid outbreaks that could shutter classrooms again.

“There was definitely an atmosphere at the beginning of summer, that we’ve come out the other end, the pandemic’s winding down and everybody’s going back to the way it was pre-pandemic,” said Michael Tkach, chief behavioral health officer for Affinity Empowering, an Alexandria, Va.-based company which provides COVID-19 testing to schools and community groups in 26 states. “Once Delta variants started really picking up … we were seeing a much greater interest in [systemic] testing programs emerge as cases continue to spike. And rightfully so, because you want to be aware of the safety of the children and the staff that you’re working with, so you can make informed decisions about what to do to help protect their health.”

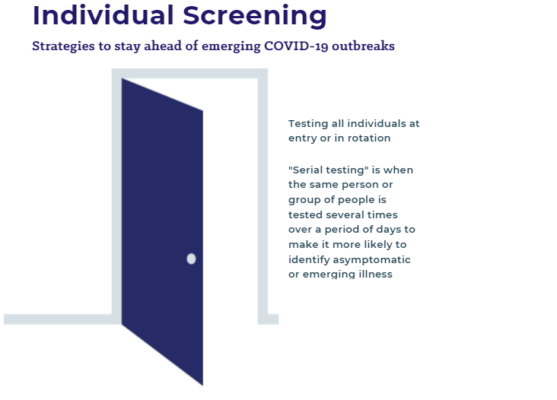

A new study released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found the Delta variant of the coronavirus first entered Mesa County, Colo., through five school-based infections and rapidly spread throughout the community. The findings mirror those of studies in other countries, which have also found Delta more likely to spread in schools than previous strains of the virus. The CDC noted that just as regular COVID-19 monitoring is needed in hospital and nursing home environments, systemic testing for K-12 and higher education is “particularly useful due to their high risk of exposure or severe illness.”

But that’s likely to be a heavy financial and logistical lift for districts that have, by and large, relied on contact tracing, temperature checks, and families reporting fevers and coughs to determine who to test and quarantine. While symptom checks have been found to reduce the risk of outbreaks—particularly when used with other safety measures such as mask-wearing, cleaning, and indoor ventilation—experts suggest more schools should consider more systemic ways to track the virus, such as regularly testing individuals or groups or monitoring markers of the virus in wastewater.

“Most systemic [COVID-19] testing has not been done in the K-12 space. The vast majority of testing has been done on the university and college level,” said Dr. Tina Tan, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Lurie Children’s Hospital in Chicago and a coronavirus expert with the Infectious Disease Society of America.

“The [CDC] recommendations are that schools should offer at least weekly testing for students that are not vaccinated in communities where you’re having moderate to high transmission—which is probably everywhere now,” she said. “And then you should also do it for teachers and staff. You can imagine that in a really big school district, if you’re trying to do this weekly in an elementary school where none of the students are vaccinated, this could really add up to very high amounts of money.”

How do tests for COVID-19 work?

The SARS-COV-2 virus belongs to the coronavirus family, which includes those viruses responsible for ailments such as the common cold. There are two basic kinds of tests to identify the specific virus (and its many variants) responsible for COVID-19:

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests look for the presence of the RNA of the virus. They require lab processing but can provide more precise genetic results, usually in about 24 hours.

- Antigen tests (also known as rapid diagnostic tests or lateral flow device tests) look for proteins associated with the viral RNA. They are less precise but usually return results in about 15-20 minutes.

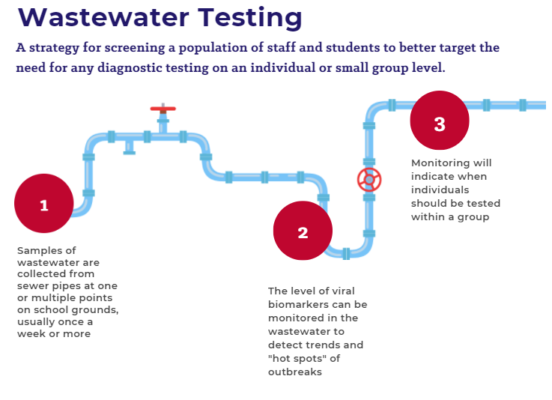

Schools can collect these samples from the students directly, swabbing a cotton stick inside both nostrils of often wincing or wriggling students. But they can also use more passive collections, such as monitoring viral biomarkers for the coronavirus in wastewater.

For example, the city of Oak Ridge, Tenn., has used wastewater sampling to monitor both overall community spread and identify hot spots for infection. The city includes several of Oak Ridge city schools in overall collection.

So far, this sort of school COVID-19 monitoring has usually been done by city partnerships like Oak Ridge’s or universities, which can target collection points in specific dorms. However, Aaron Peacock, the director of Molecular Biology for Microbac, said districts and individual schools can also track the virus through wastewater sampling at each campus or even targeted to restrooms serving particular grades.

However, he warned that these testing systems cannot pinpoint individual cases and are better to be used to look for overall trends in connection with individual testing.

Why might schools need more testing this year?

Common seasonal illnesses like the flu and respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV, which normally spread most in winter, are showing up early this fall and could complicate efforts to track COVID-19 via symptoms, Tan said.

“There’s been a shift in the respiratory viral season,” she said. “We’ve been inside for the last 15 to 18 months and the viruses had no one to be transmitted to, but now that everybody is kind of forgetting about wearing their mask and going about their business and interacting with other people, the viruses are taking advantage of that and they’re causing infection.

So it’s going to be interesting to see what happens with flu and COVID.”

The Departments of Defense and Health and Human Services in May launched the $650 million “Operation Expanded Testing” program to help schools and community groups pilot new ways of implementing systemic COVID-19 screening systems, above and beyond the federal funding to states to support testing.

Horizons, a summer academic program that uses active games and hands-on activities to teach math and reading to low-income students, was forced to go completely virtual last summer. Jaime Perri, executive director of the Horizons program at Sacred Heart University in Fairfield, Conn., said her students had more difficulty engaging in video-based enrichment, and she was hospitalized earlier this year for her own case of COVID-19, so she jumped to join the federal testing pilot when reopening in-person this summer.

“It’s so important for schools to test, especially now with this new variant that’s so highly contagious,” Perri said. “Testing is really the only way to catch it before it becomes a problem that takes the school down or has the kids quarantined at home with remote learning for the remainder of the school year. I think it’s so important for kids socially and for their well-being to be around other children, and in class, and moving around, and anything that keeps them doing that I think schools should do.”

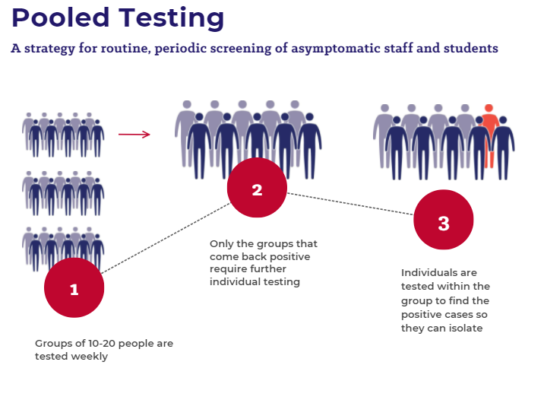

Horizons worked with Affinity to create a three-stage screening system. In addition to general symptom checks, students and staff are grouped into pools of 24 for testing. Each student gives two samples: one for themselves and one for their group. Combined group samples are analyzed first, with rapid-response tests. If a group shows evidence of coronavirus, the individual samples are used to pinpoint those who need to be quarantined.

“Children are so much more sensitive, especially since we are adults that take care of them while they’re here, but we’re not their family,” said Amanda Baez, program coordinator at Horizons. “So it was really important for us that they felt comfortable and safe and that we weren’t doing something that was so invasive, like the traditional [tests] that they stick very high up into the cavity.”

She said a nurse did the first swab and then put it into the pool test. The second swab went into the individual test marked with that student’s name. “The whole process from check-in to the end of the test took two minutes,”she said.